Beyond the Blank Page: The 10 AI Tools Redefining WordPress Product Development

The WordPress developer’s ritual is a familiar one. It begins with a spark of an…

The notification didn’t ping your phone. There was no urgent Slack message, no 3:00 AM pager duty alarm, and no frantic scramble to patch a vulnerability.

Last night, somewhere between the hours of 2:00 and 4:00 AM, a critical API dependency in your company’s payment gateway deprecated without warning. In 2023, this would have been a catastrophic morning event involving a war room, three pots of coffee, and a post-mortem apology to customers. Today? A specialized autonomous agent detected the break, read the updated documentation, spun up a sandbox environment, refactored the connection code, ran a regression test suite, and—upon achieving a 100% pass rate—pushed the fix to production.

It only messaged you once: a “Weekly Summary” email you read over your morning espresso, flagging the incident as Resolved.

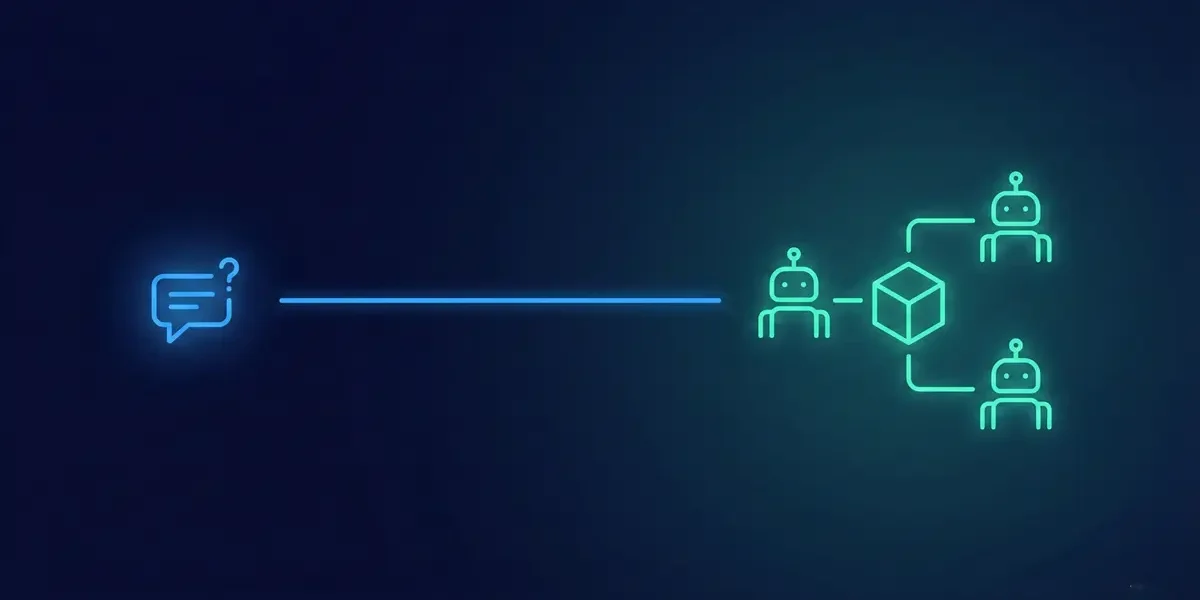

This is the promise—and the rapidly solidifying reality—of Agentic AI. For the last three years, the world has been mesmerized by Generative AI, a technology that could write poetry, debug Python, and paint surrealist art. But while we were busy marveling at machines that could talk, engineers were quietly building machines that could act.

We are witnessing the most significant architectural shift in the history of artificial intelligence: the transition from passive chatbots to autonomous AI agents. This isn’t just an upgrade; it is the difference between a consultant who gives you advice and an employee who actually does the work.

To understand where we are in 2026, we have to look back at the limitations of the “Chatbot Era” (roughly 2022–2024).

The fundamental flaw of the early Large Language Models (LLMs)—like GPT-4 or the early Claude models—was their passivity. They were stateless oracles. You asked a question, they predicted the next likely token. They had no memory of their past actions (unless fed back into the context window), no ability to manipulate the outside world, and crucially, no volition. They were brains in a jar, disconnected from the hands needed to type on a keyboard or click a mouse.

The breakthrough didn’t come from a bigger model; it came from a new cognitive architecture. It began with techniques like Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, which taught models to “show their work,” and ReAct (Reason + Act) loops, which allowed models to verbalize a thought (“I need to check the stock price”), perform an action (query an API), and observe the result.

By late 2025, these experimental loops had hardened into robust enterprise infrastructure. We stopped treating AI as a search engine and started treating it as a runtime environment for cognition.

What makes an “agent” different from a standard LLM? It comes down to three distinct components that wrap around the core model. If the LLM is the brain, these components are the hands, eyes, and ledger.

When you ask a standard chatbot to “plan a travel itinerary,” it hallucinates a list of text. When you ask an Agentic AI, it initiates a reasoning loop. It decomposes the high-level goal (“Book a flight to Tokyo”) into sub-tasks: Check calendar availability, Compare flight prices via API, Verify visa requirements, and Draft email for approval. This is often powered by Large Action Models (LAMs)—systems fine-tuned not just on human language, but on traces of software interaction (clicks, scrolls, API calls).

In 2024, connecting an AI to a database was a custom coding nightmare. By 2026, the Model Context Protocol (MCP) has become the USB-C of the AI world. It effectively standardizes how agents discover and utilize tools. An agent doesn’t “know” how to use Salesforce; it reads an MCP manifest that describes the Salesforce API, understands the inputs required, and executes the function call. This allows agents to wield calculators, code interpreters, and enterprise software suites with the dexterity of a human power user.

Unlike a chat session that wipes clean when you close the tab, agents possess persistent memory. They maintain a state of the world. If an agent tries a marketing strategy that fails, it records that failure in a vector database and adjusts its future planning. It learns from its own history, creating a compound interest effect on its competence.

The “Super Agent” fallacy—the idea that one massive AI would do everything—has largely died out. The industry has converged on a more biological metaphor: the Team.

We are currently seeing the explosion of Multi-Agent Orchestration. Just as modern software is built on microservices (small, specialized codebases talking to each other), modern AI workflows are built on specialized agents.

Imagine a software development pipeline in 2026:

Frameworks like LangGraph, CrewAI, and Microsoft’s AutoGen allow these specialized agents to debate, collaborate, and hand off tasks. If the Coder writes a bug, the Reviewer rejects it, and the Coder tries again. This adversarial loop drastically reduces error rates compared to a single model trying to “one-shot” a complex task.

Enterprises are no longer buying “AI tools”; they are hiring synthetic departments.

With the capability to act comes the risk of acting wrongly—at scale. The shift to agentic workflows has introduced a new class of cybersecurity and operational risks that we are only just beginning to mitigate.

In a chat interface, a hallucination is a nuisance. In an autonomous loop, a hallucination is a liability. If an agent hallucinates a file path and then deletes it, or hallucinates a discount code and applies it to 10,000 orders, the damage is real and immediate. This is the Loop Proliferation problem: an agent getting stuck in a reasoning error, repeating a mistake at machine speed until it drains the API budget or crashes the server.

We now have to manage “Non-Human Identities” (NHIs). Does your Customer Service Agent have permission to issue refunds? If so, up to what limit? If a hacker prompts-injects the agent, can they drain the corporate treasury? The concept of “Human-in-the-Loop” is evolving into “Human-on-the-Loop.” We are no longer driving the car; we are the driving instructor sitting in the passenger seat with a brake pedal. The challenge for 2026 is defining exactly when that brake pedal must be pressed.

We must be intellectually honest about the labor implications. Generative AI augmented creative work. Agentic AI replaces procedural work. The “middle-skills” layer—data entry, basic QA, tier-1 support, logistics coordination—is facing an existential squeeze. The economy is shifting toward valuing orchestration: the ability to design, manage, and adjudicate between teams of AI agents. The question is no longer “Can you write code?” but “Can you manage a fleet of coding agents?”

As we look toward the latter half of 2026, the boundary between “User” and “Software” is dissolving.

We are approaching a future where the Operating System (OS) itself is an agent. You won’t open Excel to analyze sales data; you will tell your OS, “Figure out why Q3 sales dropped in the Northeast,” and the OS will spawn agents to open Excel, read emails, query the CRM, and present a synthesized report.

The friction of doing is vanishing. The constraint on productivity is no longer the ability to execute tasks, but the ability to describe what you want clearly and verify the output.

The transition from Chatbot to Agent is not just a technical upgrade; it is a rewriting of the social contract between humans and machines. For the first time, we are not just using computers; we are trusting them. And as any manager knows, trust is much harder to build than technology.

The WordPress developer’s ritual is a familiar one. It begins with a spark of an…

You’ve done everything right. You have a fantastic product. You’ve built a beautiful, lightning-fast WooCommerce…

Every developer knows the ritual. You hit a wall. You need a specific WordPress hook…